Introduction

The Television Jamaica v CVM decision is the first case to have examined the protection of broadcast rights in the sporting context in the Commonwealth Caribbean. This article argues that the case represents a watershed moment in Caribbean intellectual property jurisprudence as it affirms the central role that licensing plays in the commercialisation of sport, and the increasing willingness of courts to protect the rights of sporting associations and sports broadcasters. It assesses the challenges which arise in this connection, citing, in particular, the age-old tensions between large commercial broadcasters and lesser-resourced broadcasters operating in small jurisdictions, as well as the difficulties that courts face when trying to balance the interests of broadcasters and countervailing interests involved in reporting current events and criticism and review. It argues that although the TVJ decision was rightly taken on the questions of substantiality in the context of infringement proceedings and damages in the context of the quantum proceedings, the case illustrates the need for recalibrating regional copyright legislation to reflect the American fair use criteria, given the relative inflexibility of the traditional English fair dealing defence.

Background and Context

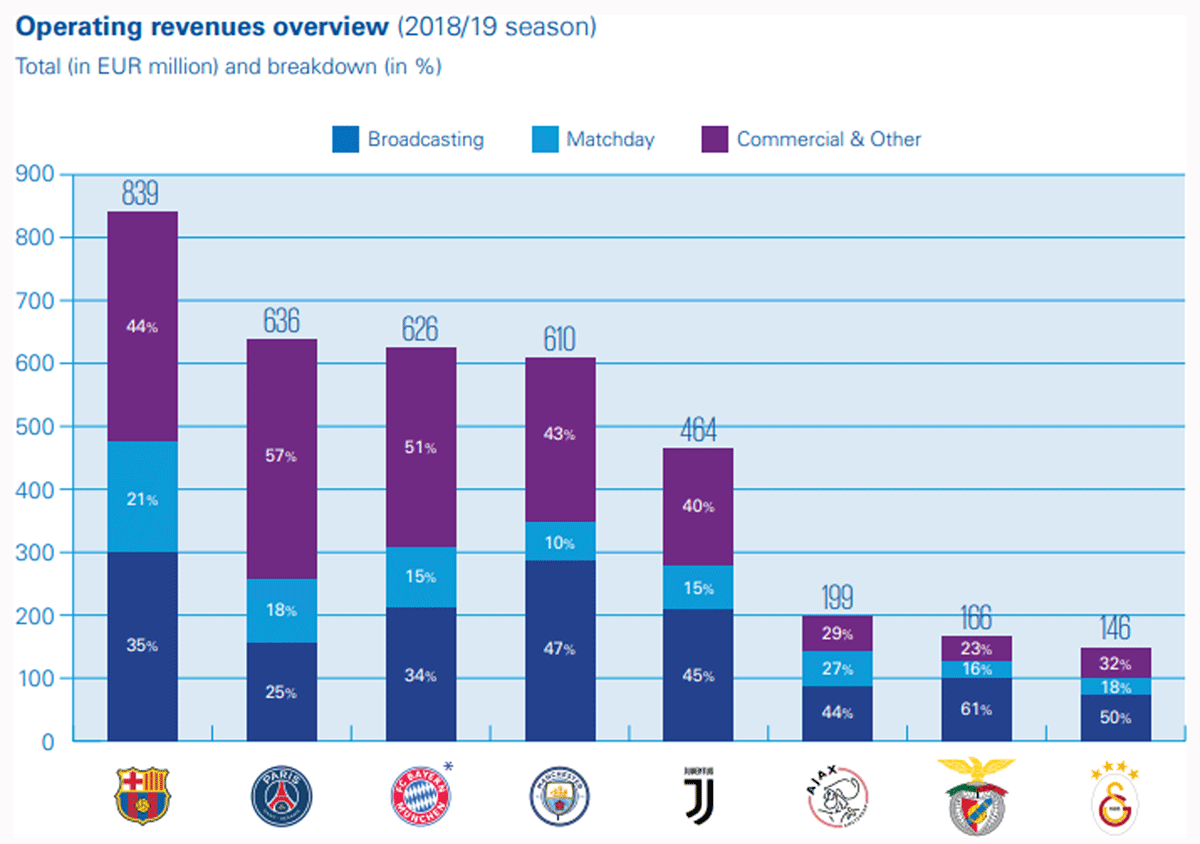

International sporting federations, leagues and clubs have traditionally relied upon three streams of income: commercial (sponsorship and advertising partnerships), match-day revenue (ticketing and hospitality) and broadcasting (sales of media rights). In the last decade, increasing commercialisation of sport and its near-ubiquitous reception by global audiences through modern forms of technology across many countries, languages and cultures have led to a significant increase in broadcast revenue.

In fact, recent statistics from the 2018 to 2019 edition of UEFA suggest that EUR 1.976B in broadcasting revenues were generated (Figure 1). Of this, FC Barcelona benefited from 298.1 EUR million; Manchester City FC 287.1 EUR million and FC Bayern München 211.2 EUR million (The European Champions Report 2020 [KPMG, 2020]).

Meanwhile, statistics from the English Premier League (EPL) shows that 2018–2019 matches were followed in 188 countries by TV audiences of 3.2 billion people. International broadcast revenue amounted to £43,184,608, whereas broadcast revenue from within the UK amounted to £34,361,519. Top broadcasting revenue earners were Liverpool with £30,104,476; Manchester City with £28,985,373; and Tottenham with £31,223,579 (O’Brien 2019).

In so far as the Cricket World Cup, England 2019, was concerned, some £400 million (Wigmore 2019) was generated in broadcast revenue, whereas more than $4 billion was generated in broadcast revenue from the hosting of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games (Chapman 2016). Although statistics on revenue generated from broadcast rights are not publicly available in the Caribbean, there is widespread acknowledgement among statisticians, sporting associations, leagues and clubs that a considerable amount of money is being earned from the broadcast of major sporting events, including the Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF) Championship, the Caribbean Premier League (CPL; Dhyani 2019) and myriad Athletic Championships.

The revenue generated from broadcast rights are used by sporting associations for a variety of laudable purposes, including the remuneration of key personnel; investment in modern technology; enhancement of stadia and other sporting facilities; and funding to support grassroots organisations, athletes and other persons concerned with the playing, management and administration of sport.

Extant Threats Faced by Broadcasters

With the magnanimous increase in the viewing of sporting events in recent years, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia, spawned on by the commensurate increased use of modern forms of technology, signal piracy has seemingly become a real problem in some countries and regions. Signal piracy, especially when committed with impunity, threatens the advertising and sales revenues of broadcasters that have paid handsomely for exclusive rights to show live coverage of sports events, and makes it significantly more difficult for public service broadcasters to sell their local content in foreign markets, especially when viewers in those markets already have access to the content through illegal Websites.

In this connection, Christopher Wood, writing for the WIPO Magazine, has explained that:

For all its benefits, digital technology has made broadcast signal piracy easy and inexpensive. Using a home computer, a pirate can capture a television station’s broadcast signal with a simple tuner card or the station’s signal streamed on line. The pirate can then stream that station’s signal on his or her own ‘channel’, using one of the popular sites that enable live streaming of what is supposed to be user-generated content. These unauthorized live streams are aggregated and distributed to a much larger universe by sites that link to or actually embed them. Some of the larger aggregation sites actually provide directories of the pirated signals. Sites that host and aggregate pirate broadcast signals are able to generate significant revenue by selling banner ads, pop-up ads, and pre-roll ads that appear before those streams, which are often placed by automated systems without regard to their legality (Wood 2014).

Such is the nature of the threat faced not only in the developed countries, but also in a number of developing countries. Writing from an Asian-Pacific perspective, Seemantani Sharma has argued that if the broadcast piracy amounted to USD 2.2 billion in the year 2010–2011 in the Asia-Pacific region, it is to be assumed that the amount has doubled or even tripped a decade later. She explains:

For developing and least developed countries in the Asia-Pacific region, broadcasting (i.e. free-to-air and pay TV) remains the primary means of mass communication. If the legitimate rights of these broadcasters are not upheld, their ability to provide these services will be severely impeded and the citizens of these countries will have no choice but to resort to alternative platforms such as over-the-top (OTT) players, like Apple TV or Netflix, which are likely to become more popular in coming years. OTT players deliver audio, video and other media content over the Internet. The problem here is that given the digital divide that exists between developing and industrialized countries, the knowledge gap will deepen because those who do not have access to the Internet will not be able to access these new digital platforms.

Public service broadcasters in many countries in the Asia-Pacific region are dying a slow death. As these countries move toward the information society, they cannot afford to let their public broadcasters fall into decline. Revenue generated by traditional broadcasters is directly proportionate to their ability to invest in the development and procurement of quality content. However, loss of revenues resulting from signal piracy impedes their ability to produce quality content. As a consequence, in the long run, the general public loses out because viewers are deprived of access to quality content and information (Sharma 2018).

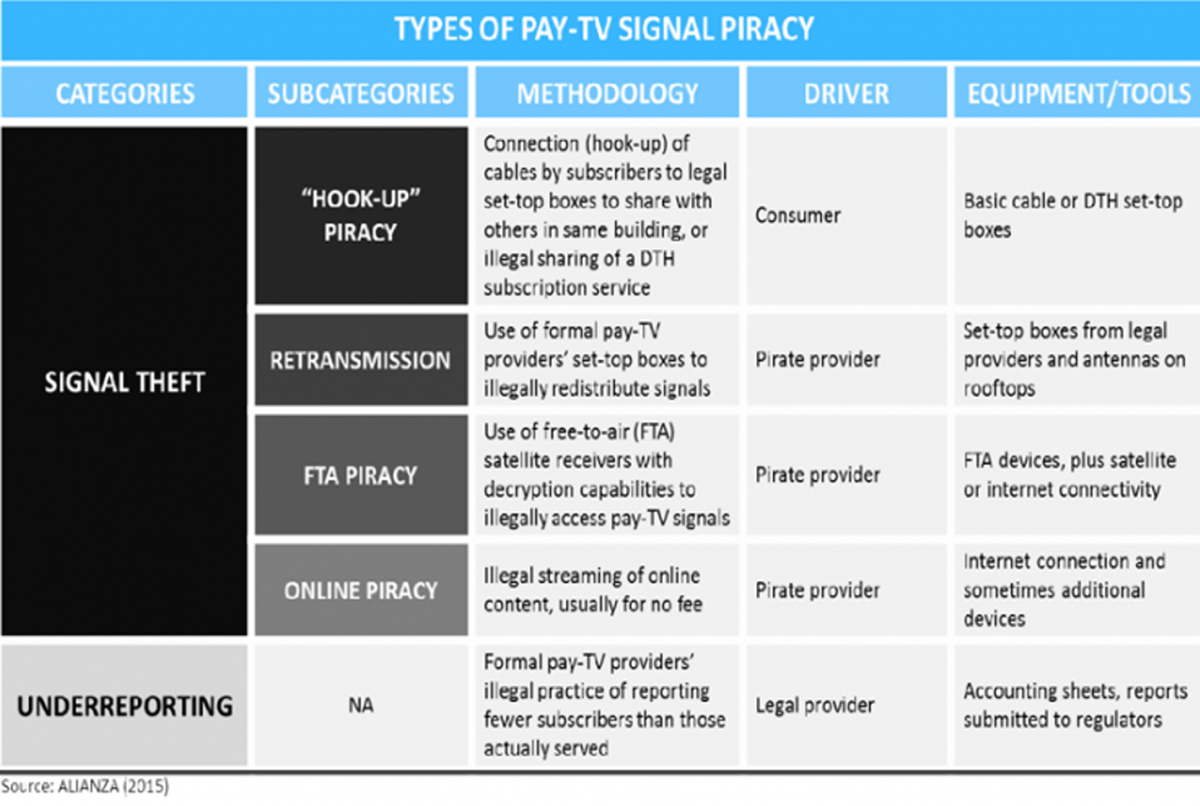

Closer to home, in Latin America and the Caribbean, it has been reported by the Alliance Against Pay-TV Piracy in Latin America (ALIANZA) that (Figure 2):

Pay-TV signal piracy is a multi-billion-dollar problem in Latin America and the Caribbean. It poses daunting challenges for pay-TV operators, programmers, governments and consumers alike.

(…) when all forms of piracy (except the online variety) are taken into account, users of stolen and underreported pay-TV signals exceed subscribers of any legitimate pay-TV service in the region. About 27% of the approximately 89-million Latin American and Caribbean households (HHs) with pay-TV enjoy it through signal piracy, excluding its online variety (Alianza Report 2019).

ALIANZA further notes that ‘hook-up’, retransmission, (free-to-air) FTA and online piracy are all forms of signal theft in Latin America and the Caribbean, in which a consumer obtains illegal or unauthorised access to pay-TV signals or audiovisual streams. It further identifies underreporting as a major issue in the region; this occurs when pay-TV operators license signals properly, but underreport the number of subscribers to their services and, as a result, pay lower intellectual property royalties and lower taxes and fees than otherwise due.

Significantly, ALIANZA has found that pay-TV providers’ total annual losses caused by signal theft, excluding online piracy, amounts to approximately USD $4.8 billion (Tables 1 and 2).

Pay-TV signal piracy penetration in Latin America and the Caribbean (excluding online piracy).

| PAY-TV SIGNAL PIRACY PENETRATION IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN (EXCLUDING ONLINE PIRACY) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COUNTRY | TOTAL PAY TV MARKET | SIGNAL THEFT | UNDERREPORTING | TOTAL PAY-TV SIGNAL PIRACY | ||

| “Hook-up” Piracy & Retransmission | FTA Piracy(1) | |||||

| HHs | HHs | HHs | HHs | %(2) | ||

| Argentina | 11,014,707 | 1,706,502 | 1,096,163 | 2,802,665 | 25% | |

| Bolivia | 792,578 | 204,726 | 203,254 | 407,980 | 51% | |

| Brazil | 24,958,393 | 4,470,960 | 1,420,628 | 5,891,587 | 24% | |

| Caribbean | 442,699 | 25,677 | 34,859 | 60,536 | 14% | |

| Chile | 3,708,233 | 230,459 | 231,291 | 461,750 | 12% | |

| Colombia(1) | 8,263,540 | 1,142,672 | 968,602 | 2,111,275 | 26% | |

| Costa Rica | 901,849 | 106,079 | 154,347 | 260,426 | 29% | |

| Ecuador | 1,970,161 | 222,463 | 268,528 | 490,991 | 25% | |

| El Salvador | 577,026 | 90,732 | 160,486 | 251,218 | 44% | |

| Guate mala | 899,437 | 178,146 | 281,340 | 459,486 | 51% | |

| Honduras | 807,829 | 174,364 | 226,291 | 400,655 | 50% | |

| Mexico | 21,631,585 | 1,463,594 | 1,483,938 | 2,947,533 | 14% | |

| Nicaragua | 494,254 | 111,526 | 144,872 | 256,398 | 52% | |

| Panama | 544,774 | 64,407 | 111,221 | 175,628 | 32% | |

| Peru | 2,953,881 | 511,670 | 326,830 | 838,500 | 28% | |

| Puerto Rico | 864,556 | 57,115 | 49,819 | 106,935 | 12% | |

| Rca. Dominicana | 1,334,919 | 282,469 | 358,675 | 641,144 | 48% | |

| Uruguay | 869,224 | 44,288 | 81,274 | 125,562 | 14% | |

| Venezuela | 6,415,675 | 857,173 | 743,510 | 1,600,682 | 25% | |

| Total | 89,445,320 | 11,945,022 | 4,000,000 | 8,345,931 | 24,290,953 | 27% |

-

(1) ALIANZA estimates that by 2015 there were at least 4 milion users of illegal FTAs in Latin America and the Caribbean. ALIANZA does not have current information to assess how those FTAs are distributed per country. ALIANZA’s FTA number is very conservative, if considered that only for Brazil, an independent study conducted by ABTA (Brazilian Association of pay-TV providers) identified 4,2 million FTA pirate devices in the market by 2015.

(2) Calculated as a percentage of the total pay-TV market.

(3) BB’s numbers for Colombia are signficantly conservative, if considered that based on 2017 official numbers published by Colombia’s National Department of Statistics (DANE) and the National Authority of Television (ANTV) the number of unreported subscribers might a mount to ~5.1 milion users.

Source: BB’s and ALIANZA’s estimates (December 2017).

Pay-TV losses caused by signal theft (excluding online piracy).

| PAY-TV PROVIDERS’ LOSSES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COUNTRY | SIGNAL THEFT (EXCLUDING ONLINE PIRACY) | ESTIMATED ANNUAL LOSSES(2) | |||

| “Hook-up” Piracy & Retransmission | FTA Piracy | TOTAL SIGNAL THEFT(1) | |||

| HHs | HHs | HHs | Annual Avg. Subscriber Fee (USD) | Pay-TV Providers’ Annual Losses (USD) | |

| Argentina | 1,706,502 | 1,706,502 | $399 | 680,484,878 | |

| Bolivia | 204,726 | 204,726 | $284 | 58,224,209 | |

| Brazil(3) | 4,470,960 | 4,470,960 | $324 | 1,448,590,889 | |

| Caribbean | 25,677 | 25,677 | $401 | 10,294,284 | |

| Chile | 230,459 | 230,459 | $404 | 93,114,785 | |

| Colombia(4) | 1,142,672 | 1,142,672 | $217 | 247,502,841 | |

| Costa Rica | 106,079 | 106,079 | $372 | 39,499,590 | |

| Ecuador | 222,463 | 222,463 | $282 | 62,814,586 | |

| El Salvador | 90,732 | 90,732 | $262 | 23,768,070 | |

| Guatemala | 178,146 | 178,146 | $172 | 30,655,338 | |

| Honduras | 174,364 | 174,364 | $144 | 25,108,426 | |

| Mexico | 1,463,594 | 1,463,594 | $201 | 293,655,570 | |

| Nicaragua | 111,526 | 111,526 | $156 | 17,438,222 | |

| Panama | 64,407 | 64,407 | $370 | 23,804,647 | |

| Peru | 511,670 | 511,670 | $281 | 143,554,166 | |

| Puerto Rico | 57,115 | 57,115 | $337 | 19,245,527 | |

| Rca. Dominicana | 282,469 | 282,469 | $225 | 63,589,390 | |

| Uruguay | 44,288 | 44,288 | $433 | 19,164,175 | |

| Venezuela(5) | 857,173 | 857,173 | $443 | 379,727,483 | |

| TOTAL | 11,945,022 | 4,000,000 | 15,945,022 | $300 | 4,783,506,479 |

-

(1) Includes BB’s and ALIANZA’s numbers for “hook-up”, retransmission and FTA piracy. Underreporting estimates are not included in this assessment of pay-TV providers’ annual losses because underreported subscribers are served by legal providers. Online piracy is also excluded.

(2) Annual avg. subscriber fee multiplied by total pay-TV signal theft.

(3) If we consider numbers published by ABTA for FTA piracy (~4.2 million), the annual losses for pay-TV providers in Brazil would increase from ~US$1,448M to ~US$2,809M.

(4) If, based on pay-TV penetration estimates published by DANE, the total amount of subscribers being served by an informal form of pay-TV amounts to ~5.1M, then the annual losses for pay-TV providers in Colombia would increase from ~US$247M to ~US$1,104M.

(5) Annual avg. subscriber fee for Venezuela as estimated by BB in 2015 and without foreign exchange rate corrections.

Source: BB’s and ALIANZA’s estimates (December 2017).

The foregoing infographics seem to suggest that piracy of broadcasts is a live issue in Latin America, albeit less so in the Caribbean. Nonetheless, the recent Caribbean case of Television Jamaica v CVM does provide a useful opportunity for consideration to be given to the scope of protection afforded sports broadcast rights in Jamaica, and the wider Caribbean, by extension. As will be illustrated in this article, the TVJ case, although progressive in many respects, nevertheless brings into sharp focus the inherent tensions that exist and which copyright law seeks to address between exclusive rights of large broadcasters versus independent sports broadcasters, and the commercial and proprietary interests of broadcasters versus ordinary viewers of sporting events.

The International Legal Framework

In a global effort to combat infringements of broadcast rights across different geographic regions, the international community adopted the International Convention for The Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organisations (‘The Rome Convention’) on October 26, 1961, to which many Caribbean countries are States Parties (WIPO n.d.). The Convention defines ‘broadcasting’, in Article 3(f), to mean ‘the transmission by wireless means for public reception of sounds or of images and sounds’.

According to scholars in this field, including Megumi Ogawa, this definition is limited to wireless transmission, such that it does not include cable (wired) broadcasting (Ogawa (2006)). Furthermore, because it mentions that the transmission must be intended for public reception, it does not include satellite broadcasting which involves transmission of a signal between a terrestrial broadcaster and a satellite (extra-terrestrial). In addition, Internet broadcasting is excluded from the definition because Internet broadcasting anticipates transmission of visual images and sounds by means of a user’s request, as opposed to the transmission being intended for public reception. Another challenge with the Rome Convention’s definition is the fact that the transmission must, of necessity, contain sounds or visual images or a combination of both; a wireless transmission that encapsulates teletext (text and graphics) appears to be excluded from the definition.

Notwithstanding these challenges, however, the Rome Convention has served the international community reasonably well over the last 60 years in that it introduced the national treatment standard (Article 6), which requires that countries treat broadcasters from other countries that are party to the Convention no less favourably than they treat domestic broadcasters. It also grants broadcasters a range of rights; it prohibits others from rebroadcasting their broadcasts; fixating their broadcasts; reproducing their broadcast without permission; and communicating to the public their broadcasts if such communication is made in places accessible to the public against payment of an entrance fee.1 These rights are afforded for a period of 20 years from the time the broadcast took place.2

Despite the wide-ranging rights outlined above, however, the Convention introduces a number of exceptions (i.e. circumstances where it would be lawful to use a broadcast), including private use; use of short excerpts in connection with the reporting of current events; ephemeral fixation by a broadcasting organisation by means of its own facilities and for its own broadcasts; and use solely for the purposes of teaching or scientific research.3

Broadcasting organisations have, for a number of decades, argued that the Rome Convention does not offer them adequate protection against infringement. They argue that the Convention is the product of an age in which cable network was at its inception, the use of satellites for broadcast transmission was unheard of and the Internet was not even a fanciful idea (Sharma 2018). For this reason, after World Intellectual Property (WIPO) members agreed to the so-called WIPO Internet Treaties in 1996, broadcasters began to press for updated protection for new broadcasting technologies. Suffice it to say, although there is broad agreement, at least in principle, that broadcasters should have updated international protection from theft of their signals, WIPO members have thus far failed to agree on how this should be done and what further rights, if any, broadcasters should enjoy.

In 2007, WIPO’s General Assembly agreed to pursue a ‘signal-based approach’ to drafting a new treaty so as to ensure that provisions on signal theft in themselves did not give broadcasters additional rights over programme content. In 2011, WIPO’s Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights, which is responsible for the broadcasting negotiations, agreed a work plan to come up with a new draft treaty that would be acceptable to all or most WIPO members.

In 2017, the Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights, at its Thirty-Fifth Session held in Geneva on 13 to 17 November 2017, discussed a Draft Treaty on Broadcasters’ Rights. The Draft defines, in Article 1, ‘broadcasting’ as the ‘transmission of a programme-carrying signal (i.e., signal transmitting sounds and/or images) by wire or wireless means for reception by the public’, whereas ‘cablecasting’ is defined as ‘the transmission of a programme-carrying signal (i.e. signal transmitting sound and/or images) by wire for reception by the public’. This definition excludes transmissions over computer networks. In terms of rights that are likely to be granted to broadcasters, the Draft makes it clear, in Article III(1), that broadcasters and cablecasters will have the exclusive right of authorising the retransmission of their programme-carrying signal to the public by any means, including communication to the public. This right will inure to them for a period of at least 50 years from the end of the year in which the programme-carrying signal is transmitted.

In so far as exceptions are concerned, Article IV (1) of the Draft postulates that Contracting Parties may, in their national legislation, provide for the same kinds of limitations or exceptions with regard to the protection of broadcasting [or cablecasting] organisations as they provide, in their national legislation, in connection with the protection of copyright in literary and artistic works, and the protection of related rights.

Quite interestingly, the Draft requires that Contracting Parties provide adequate legal protection and effective legal remedies against the circumvention of effective technological measures that are used by broadcasting [or cablecasting] organisations in connection with the exercise of their rights and that restrict acts, in respect of their broadcasts, that are not authorised by the broadcasting [or cablecasting] organisations concerned or are not permitted by law. This includes adequate and effective legal protection against the unauthorised decryption of an encrypted programme-carrying signal. In addition, the Draft stipulates that Contracting Parties shall provide adequate and effective legal remedies against any person knowingly performing acts that will induce, enable, facilitate or conceal an infringement of the broadcasting right, namely, removing or altering electronic rights management information without authority; or retransmitting the programme-carrying signal knowing that electronic rights management information has been without authority removed or altered.

The Draft Treaty has been hotly criticised for a number of reasons. First, it does not address the concerns of webcasters, that is, the issue of infringement of webcasting rights (broadcasting over the Internet or video content intended for Internet streaming). Second, the Draft Treaty contains provisions on the prohibition of the breaking of anti-piracy ‘locks’ on digital signals, such as encryption and ‘tagging’, which may have the effect of restricting what can be viewed on what equipment, thereby seemingly blocking perfectly legal uses of TV broadcasts, such as recording programmes for personal or educational uses, which may inhibit technological innovation. In addition, while some countries want protection to last for 50 years, a large number of countries have argued for no more than a 20-year term (as in the Rome Convention), since giving broadcasters such exclusive protection for an extensive period of time would likely hinder access to copyrighted material by requiring permission to use it not only from the copyright owner (such as the producer of a TV show or documentary), but from the broadcaster (WIPO 2018).

The second important international treaty that is relevant to the protection of broadcast rights is the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (‘TRIPS Agreement’). This Agreement, in Article 14(3), provides that:

Broadcasting organizations shall have the right to prohibit the following acts when undertaken without their authorization: the fixation, the reproduction of fixations, and the rebroadcasting by wireless means of broadcasts, as well as the communication to the public of television broadcasts of the same.

Where Members do not grant such rights to broadcasting organizations, they shall provide owners of copyright in the subject matter of broadcasts with the possibility of preventing the above acts, subject to the provisions of the Berne Convention (1971).

Megumi Ogawa, commenting on this provision, has noted that ‘the purpose of TRIPS is to compel WTO countries to protect intellectual property rights with comprehensive enforcement mechanisms even though they are not members of any intellectual property–related conventions. However, (…) TRIPS allows member countries not to recognise the rights of broadcasting organisations’ (Ogawa 2006). Clearly, this provision is inadequate to ensure an effective level of protection to broadcasters, as it is couched in purely hortatory terms.

The National Framework

The national legal framework on the protection of broadcast rights in the Commonwealth Caribbean is undergirded by the respective countries’ Copyright Acts and Broadcasting legislation. In general, regional Broadcasting legislation4 define ‘broadcasting’ in ways similar to the Rome Convention and Copyright Acts; outline the different types of broadcasters that may operate, namely ‘noncommercial broadcasters’ and ‘commercial broadcasters’; and outline the different types of broadcast licenses that may be applied for, namely island-wide, limited area and international relay service licences.

The region’s Copyright Acts,5 on the contrary, define a ‘broadcast’; outline who is an author/owner; the requirement for legality of broadcasts, namely the licensing requirement; the rights which broadcasters enjoy; the applicable term of protection; the circumstances that will give rise to an infringement; the remedies available where an infringement has been committed; and applicable defences. This article is intended to address the adequacy of the national legal framework regarding the protection of broadcast rights in the Commonwealth Caribbean in these areas.

Subsistence of Copyright in Broadcasts

Regional Copyright legislation typically provide that copyright subsists in a ‘work’; a work is then defined to include ‘a broadcast’, which is further defined by the respective legislation as the wireless transmission of visual images and/or sounds for reception by the public.6 This definition is largely consistent with the Rome Convention, although there are some jurisdictions which have gone further by recognising not only the transmission of visual images and/or sounds, but also ‘other information’, possibly including teletext. Other jurisdictions have also extended protection to cable and/or satellite transmission, which reflects modern developments, post-the Rome Convention. Yet still, at least one country in the region, St Vincent and the Grenadines, only extends the protection to ‘the aggregate of sounds, or of sounds and visual images, embodied in a programme.’7

The phraseology ‘embodied in a programme’ seeks to limit the protection of copyright in broadcasts in a radical fashion, reminiscent of the decision of the High Court in the Australian case of Network Ten Pty Limited v TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited.8 In that case, Ten Network had broadcast a weekly television programme entitled The Panel, which included 20 extracts from programmes previously broadcast by the Nine Network. The clips that were used in The Panel ranged from 8 to 42 seconds. Channel Nine sued, arguing a breach of copyright in their TV broadcast, whereas Channel Ten relied on the fair dealing defence. While the Full Court of the Federal Court (equivalent to Caribbean Courts of Appeal) held that copyright subsisted in each and every still image transmitted, or in each visual image capable of being observed as a separate image on television, and that one does not have to wait until there has been a transmission of enough of the images and sounds to constitute a programme before concluding that a television broadcast has been made, the Australia High Court reversed this decision, finding that:

There is no indication, as Nine would have it, that, with respect to television broadcasting, the interest for which legislative protection was to be provided was that in each and every image discernible by the viewer of such programmes, so as to place broadcasters in a position of advantage over that of other stakeholders in copyright law, such as the owners of cinematograph films or the owners of the copyrights in underlying original works.9

In other words, in their Lordships’ view, a single image extracted from a broadcast cannot be protected because copyright cannot subsist in that image; rather, only programmes that comprise multiple images and possibly sounds will be protected in Australia since those images form a substantial part of the broadcast.

This parochial approach to the subsistence of broadcast rights was rejected by their Lordships, Kirby J and Callinan J, who issued powerful dissenting judgements in Network Ten Pty Limited v TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited. Although their sentiments seemingly fell on deaf ears as the majority ruled that copyright only subsisted in visual images and sounds that constitute a programme, Justice Kirby expressed the erudite view that:

Everyone knows that still images or very brief segments in television broadcasts can constitute commercially valuable commodities, standing alone. The acquisition by a broadcaster of comparatively short filmed sequences will sometimes represent very important and commercially valuable rights that exist without the need of a surrounding context, let alone an extended programme or particular segment of a day’s broadcast.10

(…) the Full Court was right to reject the notion that the ‘visual images’ protected by s 25(4)(a) were only so protected if they constituted a ‘substantial’ part of ‘a television broadcast’.

(…) Given the terms of the Act, and the purpose of the Parliament in introducing copyright protection in the case of ‘a television broadcast’, it would be surprising indeed if the only infringement for which the Act provided was constituted by a rebroadcast of an entire television ‘programme’ or of some particular segment of such a programme to an extent yet to be specified with acceptable precision.11

(…) ‘substantial part’ of a television broadcast will not necessarily represent a segment of long duration. The image of a winning ball or a goal in a sporting final; the sight of a catastrophe captured on film by a television crew that arrived there first; the image of events of global significance akin to the collapse of the World Trade Center in New York in 2001 or the crash of the Concorde airliner, all illustrate the impossibility of thinking in such purely quantitative terms in the context of this medium.12

Meanwhile, Justice Callinan was of a similarly erudite view:

(…) What is also of significance is that the Rome Convention, to which the Attorney-General referred, by Art 13 sought to protect not ‘programmes’, however they might be defined, but broadcasts and to prohibit fixation or the rebroadcasting of fixations of them.13

I would accept that a question of substantiality may in some circumstances require consideration of the quality, importance, relevance and duration of part of a work in an appropriate case, but that it may, does not mean that the recording and rebroadcasting of a very brief segment of a broadcast is not an infringement of the broadcaster’s copyright.14

The essence of Justices Kirby and Callinan’s view is that copyright can subsist in short segments of visual images and/or sounds, depending on how important and relevant they are, and that, by parity of reasoning, copyright does not only subsists in visual images and/or sounds that are embodied in programmes.

This dissenting opinion in The Panel Case appears to have been tacitly accepted in the Jamaican case of Television Jamaica Limited v CVM Television Limited.15 Here, TVJ had, for the year 2015, the exclusive licence to broadcast the IAAF’s World Athletic Championship held in Beijing, China. In order to satisfy its viewing audience, TVJ developed and promoted their own programme called ‘Return to Beijing’. CVM, a competitor, developed its 1-hour counter-programme, ‘Return to the Nest’. CVM monitored the WAC on the IAAF’s Website and the IAAF live YouTube.com stream. It downloaded and compiled footage of the daily sessions from the live stream, including races, interviews and reactions. TVJ claimed a breach of its copyright in CVM’s unauthorised use of its broadcast. It was held that there was a breach of copyright as there was copying of a substantial part of TVJ’s broadcast without permission by CVM. On the issue of subsistence of copyright in the broadcast, the Court:

(…) assume[d] that the work comprise[d] each session and the individual events in each session. Based on this assumption, each race was a protected work (…) the work, however made up, was subject to copyright protection and one of the holders of that copyright for the purposes of this case was TVJ (…)16

Work consisted of the entire broadcast as well as individual events such as the heats in sprint events (…) the entire session whether comprised of individual events such as heats, or interviews of athletes, the crowd doing the Mexican wave, a medal presentation, anything that happened during the broadcast—from an ant crawling on the ground to a dramatic finish of track event—is covered by the exclusive licence.17 Later on in the judgement, the court considered, albeit when dealing with the defence of fair dealing, that ‘it matter[ed] not whether moving images or stills were used. TVJ’s exclusive licence covered all images, moving or still.’18

This decision, in particular, the statement ‘anything that happened during the broadcast—from an ant crawling on the ground to a dramatic finish of track event—is covered by the exclusive licence’ appears to be reminiscent of the dissenting view of Kirby J and Callinan J in The Panel case, namely that visual images may be protected, even though they do not constitute a ‘programme’. Beyond this cursory statement, the court in TVJ v CVM, however, did not meaningfully address the issue of subsistence, as there was simply a passing reference to the protected work.

Suffice it to say, while it appears clear from Football Association Premier League & Ors v QC Leisure that copyright may subsist in ‘various works contained in the broadcasts, that is to say, in particular, the opening video sequence, the […] anthem, pre-recorded films showing highlights of recent […] matches, or various graphics’,19 copyright does not appear to subsist in a sporting event or spectacle. This matter arose for consideration in the US case of Production Contrac. v. WGN Continental Broadcasting.20 Here the claimant brought an action to protect its rights in the broadcast of a Christmas parade that it had held in Chicago. Because the defendant, WGN, intended to telecast the parade, using its own personnel and equipment, simultaneously with the claimant’s telecast, the claimant sought an injunction to prevent WGN from televising the parade. The court, however, held that in circumstances where WGN would have used its own equipment, cameramen and directors, it would have created its own work of authorship in the parade telecast. This was not a case in which WGN was engaging in videotaping, tape-delays, or secondary transmission of the claimant’s broadcast. This was simply a case where the claimant’s copyright in its broadcast did not prevent another simultaneous live telecast by another television broadcaster, as copyright does not exist in the event/spectacle. Although this question has not arisen in the Caribbean context, it is very likely that this reasoning would be countenanced were the matter to arise in future before regional courts.

The Rights of Broadcasters

Broadcasters are characterised by the region’s Copyright Acts as the ‘author’ or ‘owner’ of the requisite broadcast. A number of rights have been afforded broadcasters under the relevant Copyright legislation, including the right to copy the work; issue copies of the work to the public; play or show the work in public; and rebroadcast the work.

In the same vein, the author/owner of the copyright in a broadcast can authorise a third party to do any of the foregoing acts, namely through a waiver regarding the nonenforcement of its rights, or a license agreement. The license agreement, in particular, will spell out the terms and conditions under which the licensee can engage in any of the forgoing acts, and limitations thereto, as well as provide for the payment of a license fee.

Nowadays, licensing is one of the primary ways through which authors/owners of copyright in a broadcast seek to monetise their IP asset. In practice, a license is awarded to broadcasters under an open competitive tender procedure which begins with the invitation to tenderers to submit bids on a global, regional or territorial basis. Demand then determines the territorial basis on which the owner of the copyright in the broadcast sells its broadcast rights. However, as a rule of thumb, that basis is national since there is only a limited demand from bidders for global or pan-European or pan-Caribbean rights, given that broadcasters usually operate on a territorial basis and serve the domestic market either in their own country or in a small cluster of neighbouring countries with a common language. Where a bidder wins, for an area, a package of broadcasting rights for the live transmission of the sporting event, it is granted the exclusive right to broadcast them in that area. This is necessary, according to owners of broadcast rights, to realise the optimum commercial value of all of the rights, broadcasters being prepared to pay a premium to acquire that exclusivity as it allows them to differentiate their services from those of their rivals and therefore enhances their ability to generate revenue.

As the court noted in Television Jamaica Limited v CVM Television Limited,21 bringing a broadcast to a particular territory is a costly endeavour, which justifies the protection afforded broadcasters under the Copyright Act:

In order to recover its expenditure and also make a profit, TVJ has to secure sponsorship and advertisement. One of the things that makes this kind of event attractive to sponsors and advertisers is the ability to say to them that this product is exclusive to TVJ. The idea being that because the WAC has such a fanatical following in Jamaica, any broadcaster who secures the exclusive licence has potentially an attractive product that can be used to entice (or I should say interest) commercial entities to purchase slots during the exclusive broadcast in order to advertise their goods and services.

The sponsor is the mega advertiser. The sponsor is the crown jewel in the broadcaster’s crown. The advertiser is, well just that an advertiser. Every sponsor is an advertiser but not all advertisers are sponsors. The sponsor is the big spender. The sponsor is offered a package in exchange for a huge sum of money. It is usually a large company with a significant advertising budget. What does the sponsor get in exchange for its mega dollars? Its banner and logo are displayed in studio. Its name, product and tagline are splashed across the screen at the beginning and end of each broadcasting session and at each break within the session. For example, a broadcast session may last three hours. At the beginning and end of each session the name, product and tagline are transmitted. Within each session there are breaks for advertising. It often happens that just before the break and just on the resumption, the sponsor is announced and its product seen. There is virtually no limit to this. All this is part of package that the sponsor pays for once. On the other hand, the advertiser who is not of sponsor status has to pay for each broadcast of its goods and services. He purchases specific times both in terms of the length of the advertisement and the time slot. He gets no banners and the like.22

In order to protect territorial exclusivity, licensees typically undertake, in their license agreement with the owner of the broadcast, to prevent the public from receiving their broadcasts outside the area for which they hold the license. The legality of these ‘exclusive territorial licensing clauses’ arose for consideration in Football Association Premier League & Ors v QC Leisure,23 in which it was held that although, in principle, exclusive territorial licensing clauses do not offend the freedom to provide services, as contained in Article 56 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), nor freedom against anticompetitive business conduct, as contained in Article 101 of the TFEU, the imposition of additional restrictions would be unlawful under EU law. These ‘additional restrictions’ to which the European Court of Justice (ECJ) referred to include the prohibition of the importation of foreign decoder cards obtained in one jurisdiction and thereafter used in another EU jurisdiction in circumstance. This is because this prohibition had the effect of re-establishing national borders to the provision of services at the pan-European level which the TFEU was intended to dismantle, and were thus not necessary to achieve the objective of protecting broadcast rights.

In the Caribbean context, the court in Television Jamaica Limited v CVM Television Limited24 did not engage in a robust discussion on the legality of exclusive territorial licensing clauses. Its mere passing remarks on TVJ’s role as exclusive licensee in the territory of Jamaica to the exclusion of all others, however, do suggest that these agreements may not be prima facie unlawful. Suffice to say, it would be interesting to see how the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), the region’s highest court concerned with the interpretation of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas (RTC), treats with broadcast licensing agreements that impose additional burdens (e.g. prohibitions on the importation and sale of foreign decoders and prohibition on licensees responding to customers in other CARICOM countries that request their services),25 in light of Articles 36 and 37 of the RTC, which prevent the imposition of new restriction on services as between CARICOM member states, and require states to abolish discriminatory restrictions; and Article 177 of the RTC, which prohibits anticompetitive business conduct engaged in by companies in the CARICOM region.

Infringement

In general, under Commonwealth Caribbean Copyright legislation, an infringement of copyright occurs where a third party, without permission, copies the whole or a substantial part of a broadcast; or issues copies of it to the public; or plays or shows it in the public; or rebroadcasts it.

In circumstances where a third party has taken and used a substantial part of a broadcast in an unauthorised fashion, the court will likely find an infringement. This notion of a ‘substantial part’ is a ubiquitous concept that has been interpreted variously by tribunals as referring to, among other things, whether what has been taken amount to ‘essentially the heart’ of the copyrighted work; ‘the essential part of the copyright work’; ‘an important ingredient’ of the copyright work; ‘the best scenes from the programme’; ‘highlights from the programme’; ‘central to the programme in which it appeared’; and ‘the “heart”—the most valuable and pertinent portion—of the copyright material’.

The question of substantiality in the context of infringement proceedings arose in Television Jamaica Limited v CVM Television Limited.26 Here, CVM’s counter-programme, ‘Return to the Nest’, was created by CVM in the absence of a license to broadcast the IAAF World Championship in 2015. CVM was accused of downloading and broadcasting entire races and/or events or parts thereof without the authorisation of the TVJ, the exclusive licensee. The Court held that the defendant breached the copyright in the claimant’s broadcast by copying and rebroadcasting a ‘substantial part’ of the broadcast. On the issue of substantiality, the court, in similar vein to TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited v Network Ten Pty Limited27 and England and Wales Cricket Board Ltd & Anor v Tixdaq Ltd & Anor,28 considered that quantitative and qualitative considerations undergird the test for substantiality:

The total time of footage shown was approximately 11 minutes. The total broadcast time included advertisements. The clips used were significant in terms of total time and significant in terms of the parts of the races (those were parts of the races were shown) and significant in terms of the fact that all the races for the men’s 100 m heats were shown. In the world of copyright very significant portions has both a quantitative and qualitative dimension to it. The last 10 metres of a race is very significant because the last 10 metres will show the medal winners. This is track and field’s equivalent of goals and near misses of football. It is ultimately that type of information that many members of the viewing public want to know.29

In its determination of whether an infringement had occurred, the court was confronted with a difficult question, which had not previously been addressed in cases decided upon in other jurisdictions, namely, the argument advanced by the defendant that it did not actually take the clips from TVJ’s broadcast, but from the IAAF’s YouTube stream. In response to this difficult question, the court considered that:

(…) it is no defence to say that the infringement did not actually involve taking, in this case, the live or delayed TVJ broadcast. In other words, the infringer cannot say in defence, ‘I got the material from somewhere else and not from TVJ’s actual broadcasts. I did not intercept any broadcast signals intended for TVJ or neither did I feed into TVJ’s broadcast after it received the broadcast signals.’ Once a person, natural or otherwise, has an exclusive licence then no other person, natural or otherwise, can do any of the acts the exclusive licensee can do by accessing the exclusively licenced material from some other source unless there is a legal exemption or lawful excuse.

The value of the court’s foregoing judgement lies in the fact that it is the first sporting case in the context of the Commonwealth Caribbean to definitively address the circumstances in which a sports broadcaster (B) may infringe the rights of another broadcaster/licensee (A) where the infringing broadcaster (B) copied clips from the licensor’s (C) streaming platform. The case clarifies that the law places a high premium on the substantial investment, which broadcasters pay sporting organisations to be able to exclusively broadcast sporting events, while articulating the willingness of courts to countenance claims by broadcasters against other broadcasters, irrespective of whether they are large-, medium- or small sized, where their copyright is perceived to have been infringed. Unlike the state of affairs which obtained in the past wherein broadcasters in the Caribbean largely turned a blind eye to the copying/rebroadcasting of their material, this case demonstrates a paradigm shift in which broadcasters are increasingly becoming more vigilant and proactive in the protection of their commercial interests. In this connection, a broadcaster which does not have a license or sublicense, but which wishes nonetheless to broadcast elements of the broadcast, such as interviews and highlights of elements of the sporting event, must carefully consult with their lawyers to ensure that they do not infringe upon the rights of the exclusive licensee. The time when infringing broadcasts escaped judicial scrutiny under the cloak of ‘news’ has seemingly elapsed as courts are now more minded than ever before to interrogate the bona fide nature of the broadcast in question, and its impact on the right holder’s proprietary rights.

The case is also instructive on the question of the appropriate test to be countenanced when determining whether an infringement has occurred in sports broadcasting cases, a novel matter in the Commonwealth Caribbean context. In TVJ, the court usefully affirmed that it would not simply focus on copying in a quantitative sense, but will also account for copying in a qualitative sense when assessing infringement. This approach is consistent with a number of recent sports broadcasting cases which have adopted the qualitative-quantitative schema, and makes good sense as a practical matter. Indeed, the outcome of the TVJ case would have been fundamentally unfair and indeed problematic from a jurisprudential perspective if the court were to have focused exclusively on the quantitative test for establishing infringement since very little quantitatively, by way of duration of clips from the claimant’s broadcast, was copied by the defendant. In fact, in some instances, the clips copied from the defendant’s broadcast were no more than 10 seconds. If only a quantitative test of substantiality was to have been countenanced by the court, none of these acts would have amounted to an infringement, even though they might have involved copying of some of the most important or essential elements of the broadcast, such as finishes of the respective athletic events. Furthermore, a quantitative approach would have effectively offered copyright protection to broadcasters in all cases where portions of their broadcast are used, even though those portions may not be important, or central, essential or the heart of the broadcast in question. By the same token, if the court had adopted a purely qualitative approach, once the clip that was copied by the defendant from the claimant’s broadcast was ‘important’, the defendant’s conduct would amount to an infringement, even though the clip may, in terms of its duration, be nothing more than a momentary or passing reference.

As such, to ensure that broadcasters do not monopolise the broadcasting market by being able to bring a claim for every use, particularly of unimportant or inessential material, by the defendant of the claimant’s broadcast, the court quite correctly adopted the quantitative-qualitative schema, which is a welcome development that sets a sound jurisprudential precedent for future cases.

Defences

There are a number of defences that are available under the respective regional Copyright Acts where an infringement in the copyright in a broadcast has been made out, namely use of the broadcast in the course of providing instruction and for educational purposes; time-shifting (namely making for private and domestic use a recording of a broadcast solely for the purpose of enabling it to be viewed to at a more convenient time)30; and fair dealing for the purposes of criticism or review or the reporting of current events.

In determining whether a defendant has made out the fair dealing defence, the court will generally take account of a number of statutorily prescribed factors, including the nature of the broadcast in question; the extent and substantiality of that part of the broadcast affected by the defendant’s act in relation to the whole of the broadcast; the purpose and character of the defendant’s use; and the effect of the defendant’s act upon the potential market for, or the commercial value, of the broadcast.

The issue of fair dealing also arose for judicial consideration in Television Jamaica Limited v CVM Television Limited.31 This case addressed the question as to whether two of CVM’s programs (‘Return to the Nest’ and ‘News Watch’), which included portions of TVJ’s broadcast, could nonetheless be exempted from infringement on the basis that they were used for ‘fair dealing’ purposes, namely reporting current events and criticism and review.

The court began its very comprehensive, nuanced and progressive analysis by making it clear that broadcasters do not enjoy a monopoly with regard to their broadcast. In this connection, it said:

(…) the absolute monopoly that broadcasters had over their undoubted copyright protected material no longer exists. The legislature broke it and created a fair dealing defence for the purpose of reporting current events. This is exactly what has happened in Jamaica.32

Quite significantly, the court pointed to the fact that under the current dispensation, not only can broadcast organisations rely on the fair dealing defence, but also ordinary citizens, in relation to whom there was previously a lack of clarity as to whether the defence inures to their benefit. Quite progressively, the court affirmed the English decision of England and Wales Cricket Board Ltd & Anor v Tixdaq Ltd & Anor33 when it found that:

(…) when the Berne Convention came into being, social media did not exist, the ‘citizen journalist’ was not clearly recognized even if he or she existed in the nineteenth century. The Berne Convention had in mind governmental or formal news agencies.34

In respect of [the fair dealing defence], this court is of the view that firstly, the [defence] is one of general application to all citizens. There is nothing in section 53 [of the Copyright Act] and the rest of the statute that precludes an ordinary person from running a blog, a vlog or some other form of communication on social media for the purpose of criticism or review of a protected work. Equally, there is nothing in the provision that precludes an ordinary person from reporting on current events. The word ‘reporting’ in the phrase ‘reporting current events’ simply means giving an account of some event. The expression ‘reporting current events’ means giving an account of something that is happening now or if it has occurred in the past is sufficiently connected to present events to make it properly part of current events. For example, the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001 can properly be regarded as a current event if sufficiently connected to a present event such as the recent attacks in Paris.35

(…) There is no reason why an ordinary citizen unconnected with any news organisation cannot report on a current event. There is nothing in the section that restricts the act of reporting to journalists or news reporters. The wording is sufficiently wide to include ordinary citizens, even though the framers of the law had in mind news organisations. Thus in this regard this court agrees with Arnold J on the result but not the route to the result.36

The next significant point made by the court, which appears to be wholly progressive and consistent with previous case law, such as British Broadcasting Corp v British Satellite Broadcasting Ltd,37 is that sports news can be properly be characterised as ‘news’ for the purposes of the fair dealing defence. In this regard, it considered that:

(…) sports news reporting can be regarded as genuine news albeit of a sporting character; [and] the wording of the section is not to be restricted to general news reporting.38

Sporting news is as much news as the usual form of news that tell us of the latest atrocity of criminals, failed banks, successful business launches, the peccadillos of public figures, the virtue of the ordinary man and the most recent earthquake [sic] or other natural disaster.39

On another note, one of the more difficult questions that arose in TVJ v CVM case was whether CVM could rely upon the fair dealing defence given that its competing programmes were created for a special occasion, namely, the 2015 World Athletics Championships. To this question, the court adopted a refreshingly liberal approach by concluding that:

[the fact] that a programme [was] specially created for a current event does not necessarily [result in the defendant] los[ing] the ability to rely on section 53 (…) if the programme is more about giving information than for consumption based on its intrinsic commercial value then the defence is made out.40

It is this court’s considered view that for the fair dealing defence to apply it is not necessary that there should already be in existence, prior to the alleged infringing use, any news programme such as Prime Time News on TVJ, or News Watch on CVM or the like. To make that a requirement would be to reduce the ambit of the provision when the words do not require such an interpretation and neither is there any policy reason for imposing that limitation on the words of section 53.41

A related issue arose for the court’s attention, namely—what if the programme in issue is a rival programme? To this, the court’s response was that:

(…) the fact that a rival is doing the reporting on current affairs is nothing to the point. It is whether the dealing is fair.42

If the programme is a true reporting of current events then it is nothing to the point to say that the alleged infringer is making the programme attractive to viewers.43

Yet another interesting question addressed by the court was what test should be adopted in determining whether the fair dealing defence was made out. In keeping with jurisprudence from other jurisdictions, the Court, quite rightly, applied the quantitative-qualitative dichotomy, ultimately finding that:

(…) in determining whether fair dealing has been established, the court must have regard to the quality and quantity of protected material that was used and its purpose. The defence of fair dealing is not lost simply asserting that the infringer took large portions from the work but depends on whether what was taken was ‘reasonably requisite’ for the purpose.44

The court then turned its attention to the statutory factors, mentioned above, which should inform its analysis on the fair dealing defence:

(…) no one factor [is] decisive. The determination of whether there was fair dealing is an intensely factual question. Each case stands on its own. What is significant in one case may well be not so important in another. This is why the trial court must actually view the material or as much of it as is possible (…)

The length of the extract, the part that is extracted, the type of programme, how it was promoted, the purpose of the programme are all important matters. What is to be prevented at the end of the day is the defendant taking the claimant’s protected work and treating as it were his own and trying to pass of his misuse as fair dealing. As should be clear from the cases it is often a close thing. The ultimate decision one way or the other is not precise as in mathematics but a judgment call based on the overall impression the court is left with after taking into account all the relevant factors of the particular case.45

Applying these factors to the facts at hand, the court found that, in connection with CVM’s ‘News Watch’, this nightly news broadcast that showed TVJ clips, namely the full 200m men’s final and the full 400m women’s final, the three men’s 110m high hurdles semifinal, involved fair dealing for reporting current events. In articulating a balanced approach, the court considered that the sports news in question was ‘equal in status in every respect to regular news’,46 and that, accordingly, the 2015 WAC was a current event. It found that CVM’s ‘News Watch’ was purely informatory in nature and purpose, and, in any event, the amount of the protected material used was not excessive. In other words, the programme was ‘not intended and could not in any rational sense be regarded as a commercial product designed to undermine TVJ’s copyright.’47 In coming to this reasoned conclusion, the court expressed the view that:

[it was] required to ask itself, was this genuine, good faith and bona fide reporting or is it commercial utilisation of another’s protected work masquerading as reporting? The answer depends on duration of the segment, what came before and after it, how was it presented, was it being presented as a substitute for the protected work, the degree to which the challenged use competes with the exploitation of the copyright by the copyright holder or as in this case the licence holder, the whole circumstance is looked including the fact of an exclusive licence.48

The court accepts that showing the entire race is a substantial part of the event. This is on the basis that each race constitutes an event and also on the basis that showing the finish alone would be a substantial part of the event. The court concludes that the purpose and character of the use was for reporting purposes solely. The 2015 WAC was of great importance to Jamaica. Track and field has been Jamaica’s most successful sport. Many Jamaicans have a keen interest in the performance of their sporting heroes and heroines.49

It is difficult to see what adverse effect the News Watch broadcast could have on the potential market or commercial value of the work. The court does not agree that the quantity and quality of the clips exceeded what was appropriate for the report. The court does not agree that the clips were wholesale appropriation of substantial parts (meaning amount and not just an important segment, for example the last 10 metres of the 100m final men’s and women’s) of TVJ’s work under the guise of reporting current events. No sensible person could consider that instead of watching TVJ’s broadcast he or she would tune in to CVM’s News Watch.50

It is the finding of this court that the section 53 defence has been established. The manner in which the footage was packaged, the context in which it was presented it is clear that it was a pure reporting of a current event. Yes, CVM is a private company set up for the purpose of making money from broadcasting and in that broad and generic sense there was commercialisation of the clips, but that is not what is meant when the law speaks of whether the infringer’s use was a commercial competitor to the rights holder’s ability to exploit his copyright or rights received under licence. The total amount of the footage in the hard news segment and the sports news segment was approximately 175 seconds. The sports news segment gave a summary of other finals and showed approximately 10 to 12 seconds of the women’s 400m final, a jump of the winner of the men’s long jump and the winner of the women’s hammer. All this is consistent with reporting a current event and not capturing the copyright holder’s work.51

Suffice to say, on the question of whether CVM’s other programme, ‘Return to the Nest’, represented fair dealing for reporting current events, the court arrived at an entirely different conclusion. In this regard, the court considered that this was a counter-programme, which was created by CVM in the absence of CVM having the exclusive licence to broadcast the WAC. More than this:

It seem[ed] clear to the court that this broadcast was not reporting as the term is commonly understood in this context. The term ‘reporting’ in this context means giving an account of something. That is to be its primary focus. It is undoubtedly true that a discussion and analytical programme can have an element of reporting but that would be incidental to the programme’s purpose. The element of reporting would be usually to give the basic facts of what is to be discussed and/or analysed and in that sense there is reporting, and where the event is current then it could be said to be reporting current events. However, it would give the programme an incorrect nuance if it were to be described as a report of current events.52

This court concludes that CVM’s broadcast of August 22, 2015 was not primarily for the purpose of reporting current events. The use of the clips was not for the purpose of fair dealing for reporting a current event. The fair dealing defence therefore fails. This conclusion applies to the entire series of ‘Return to the Nest’.53

One of the important hallmarks of the judgement in TVJ v CVM that must not go unnoticed is the court’s exemplary and progressive treatment of the nuanced issue of the posting of clips from TVJ’s broadcast on CVM’s Social Media platforms, namely its Twitter and Facebook pages. On this question, the court, while accepting that the fair dealing defence must be given a ‘liberal interpretation’, found that the social media postings that consisted solely of interviews with Jamaican athletes, which were not in the context of reporting the event, could not be characterised as fair dealing.

Interestingly, the court was mindful that its ruling was very likely to have a lasting effect on how future courts in the Caribbean construe the fair dealing defence; in this regard, it was careful to conclude that:

If the court were to hold in favour of CVM on the interviews then it would be setting the stage for unrestricted utilization of interviews without the need for any context such as reporting on current events. The interviews were not reporting and therefore they were in breach of TVJ’s exclusive licence.54

The decision in TVJ v CVM is reminiscent of the judgement in England and Wales Cricket Board Ltd & Anor v Tixdaq Ltd & Anor,55 where the English court similarly dealt with the posting of clips from the claimant’s cricket broadcast, without permission, on the defendant’s social media platforms, the ‘Fanatix’ app. In that case, the English court, while accepting that contemporaneous sporting events (i.e. cricket matches) are current events, nonetheless found that the clips were not used to inform the audience about a current event, but were presented for consumption because of their intrinsic interest and value. In other words, the defendants’ objective was purely commercial rather than genuinely informatory, and so could not rely on the fair dealing defence. The English court’s conclusion was buttressed by some important considerations, namely, the defendant’s use of the clips conflicted with the claimant’s normal exploitation of the broadcast since the unauthorised posting of the clips reduced the attractiveness of Sky’s cricket offering to subscribers; the clips damaged the claimant’s own service because licensees were reluctant to commit to paying a large sum for use of the clips when they were already made available freely to the public by the defendant; and the clips were made available on a near-live basis by the defendant. In addition, despite the relatively small scale of the use in a quantitative sense, the defendant’s apps were clearly designed to be used by very large numbers of users, as the defendants were seeking to attract as many users as possible. In short, the purpose of the use was not informatory, but for consumption; it was, therefore, not for reporting current events, but for sharing the clips of footage from sporting events.

Despite its comprehensive and progressive approach to most issues that arose for its consideration, one regrettable aspect of the TVJ v CVM decision, however, is that it did not address in any meaningful way whether fair dealing for criticism and review was actually made out on the facts. Arguably, though, the court did not have to make a ruling on this issue, as counsel for the defendant did not raise the matter as part of its defence. That said, in light of the little that was said by the court, even in its obiter statements, in relation to criticism and review, we remain unsure as to the precise scope of the fair dealing defence for criticism and review in a Caribbean context, although we can certainly draw from courts in other jurisdictions which have meaningfully addressed the issue. In TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd & Anor v Network Ten Pty Limited,56 for example, the court considered that in assessing whether a defence of fair dealing for the purpose of criticism and review is made out, it is necessary to have regard to the true purpose of the critical work. In this context, one must ask:

(…) is the program incorporating the infringing material a genuine piece of criticism or review, or is it something else, such as an attempt to dress up the infringement of another’s copyright in the guise of criticism, and so profit unfairly from another’s work? As Lord Denning said in Hubbard v Vosper [1972] 2 QB 84 at 93, `it is not fair dealing for a rival in the trade to take copyright material and use it for his own benefit.’57

The court in TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd & Anor v Network Ten Pty Limited noted that criticism or review may be unbalanced or strongly expressed and nevertheless fall within the defence, but that it has to be recognisable as criticism or review. It further explained that although criticism and review are words of wide and indefinite scope which should be interpreted liberally, the criticism and review that is contemplated by the Copyright Act involve the passing of judgement. Quite significantly, the court made it clear that criticism and review may be strongly expressed, but that, in all circumstances, it must be genuine and not a pretense for some other purpose. In other words, an oblique or hidden motive may disqualify reliance upon the defence of fair dealing for the purpose of criticism and review, particularly where the copyright infringer is a trade rival who uses the copyright subject matter for its own benefit. Finally, the court considered that criticism and review extends to thoughts underlying the expression of the copyright works or subject matter.

On reflection, it is submitted that the court’s treatment of the fair dealing defence in the TVJ case was largely consistent with extant jurisprudence, and arguably strikes a fair balance between the commercial interests of broadcasters, on the one hand, and the interests of third parties, including citizen journalists, on the other. First, the court’s recognition that copyright law does not per se preclude counter-programmes that are specifically created for special sporting occasions is welcome as it acknowledges that these programmes, if operationalised in a bona fide fashion, can offer very useful alternative thoughts and opinions about sporting events. These programmes may also cater to the differing needs of sporting audiences; the audience viewing the counter-programme are often professionals with little free time to view sporting events in their entirely, and would therefore much prefer short synopses of events that are informed by analysis by knowledgeable analysts. The court’s ruling in the TVJ case makes it clear that broadcasters of these programmes are not precluded from relying on the fair dealing defence.

A second take-away from the TVJ decision is that copyright law welcomes the participation of citizen journalists in reporting on sporting events even in circumstances where they use copyright material, provided that their purpose is informatory in nature. In this context, the court appeared to have implicitly countenanced the view that not only is human rights law capable of generous and evolutionary interpretations that address contemporary issues that confront society, but so too is copyright law, which, as the court indicated, must respond to the plight of an evolving class of citizen journalists. The court’s view that citizen journalists could obtain protection through their reliance on the fair dealing defence in appropriate cases is a welcome development that demonstrates the ability of copyright law to respond favourably to the inherent tensions between the monopolistic tendencies of broadcasters and the legitimate interests of citizen journalists.

Thirdly, the court’s substantive engagement with whether the fair dealing defence was satisfied on the facts was satisfactory, and fully in keeping with extant jurisprudence. In the TVJ case, the court considered the purpose behind the defendant’s use of the claimant’s copyright material (commercial vs informatory); the extent to which the defendant acted in good faith; the length of the clips used (use of small portions vs excessive use vs wholesale appropriation); the importance of the activity that was broadcast in the relevant jurisdiction (in this case, athletics was deemed to be of great public importance in Jamaica); the part of the claimant’s broadcast that as extracted, having regard to what came before and what came after (in this case, the majority of the clips that were extracted from the claimant’s broadcast represented important parts of the events, including the last 10 metres of races); the type of programme (in this case, a counter-programme); and how it was promoted/presented/packaged (it was packaged in a commercial manner, containing extracted interviews, to generate as maximum a viewership as possible). The court did not consider these factors in isolation but examined them collectively so as to be able to form an ‘overall impression’.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, a careful reading of the TVJ judgement affirms the relative rigidity of the extant fair dealing defence which pervade Commonwealth Caribbean jurisdictions’ copyright laws. Indeed, much of the court’s time was spent assessing whether the use adopted by the defendant fitted into the narrow categories of reporting of current events, and criticism and review, albeit to a lesser extent.58 Where the material copied by the defendant did not properly fit the mould of reporting of current events, such as the interviews in question, the court need not even address the second question as to whether the use in question was fair. This is arguably a rather restrictive approach, at least when compared to the American fair use exception whose concern is much less whether the material was used for the purpose of reporting current events or criticism and review, and is more concerned about whether the use in question is fair, having regard to a list of four statutory factors59 that are flexibly applied by courts. These factors are the purpose and character of the use; the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount or substantiality of the portion used; and the effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the work. In addition, recent jurisprudence have introduced the notion of ‘transformative use’ which now increasingly informs courts’ assessment of whether the fair use defence is made out in the United States.

In short, then, despite the detailed and robust discussion of the fair dealing defence in the TVJ case, it still holds true that the fair dealing exception is less flexible and less suited to the digital age than an open-ended fair use exception (Katz 2021). This is not a criticism of the court per se, but rather the Copyright Act itself which established defined categories such as ‘reporting current events’ and ‘criticism and review’, categories which necessarily involve some degree of ‘uncertainty and expense because of the need to identify a particular category or pigeon hole in which to fit a contested use and argument over whether the use meets the criteria for that category’ (Australia Law Reform Commission 2014).

Remedies

Regional Copyright legislation provide for a range of remedies which may be sought in circumstances where an infringement of copyright in a broadcast is made out. Among other things, these legislation provide for the grant of damages, injunction,60 and accounts of profit. Where the infringement is innocent on the part of the infringer, meaning that the defendant did not know and had no reason to believe that copyright subsisted in the work to which the action relates, then the broadcaster is not entitled to damages against him, but this is without prejudice to any other remedy.

In relation to the infringement of broadcast rights, the primary remedy that has been sought to date by broadcasters in Australia, the USA and the UK, and, indeed, in the Commonwealth Caribbean, is damages. Damages seek to put the injured broadcaster back in the position it would have been had the infringement not been committed. This point was made in Television Jamaica Limited v CVM Television Limited,61 where the court held that TVJ, as the exclusive licensee, could bring an action for damages for breach of its exclusive licence as if it were the copyright holder and there was no legal necessity for there to be an assignment, and, crucially, there was no need to join the copyright holder as a nominal claimant. The Court then indicated that, in so far as the quantum of damages were concerned, it would use as a guide the payment of licence fees. In the court’s view:

Since the evidence is that a sub-licence fee may be based on the costs of bringing the broadcast to the country in question the court is prepared to use this method in the absence of any other information. The fact that TVJ did not lose any sponsors or advertisers arising from CVM’s unlawful actions does not mean that it suffered no damage. One damage that it suffered was not earning from a sub-licence which CVM would have had to purchase if it wished to use any content from the 2015 WAC.62

The court accordingly decided that damages on the premise of a 50/50 shared cost to bring the broadcast to Jamaica and the cost of the rights itself was appropriate, such that TVJ was awarded US$85,975.00.

Meanwhile, in so far as the deliberate and calculated risk taken by CVM in airing the ‘Return to the Nest’ programme was concerned, the court felt that this was an appropriate case for the award of additional damages. In this regard, it held that:

Additional damages are not confined to circumstances where the infringer made a financial profit (…) additional damages may be awarded in case of deliberate infringement.63

(…) CVM was quite aware, if it had not known before, that TVJ had the exclusive licence to broadcast in Jamaica. Since CVM persisted in that conduct in light of the information it now had then surely the most reasonable conclusion is that its conduct was deliberate. It was prepared to take the risk in the face of the exclusive licence holder raising objections. Even before the complaints, CVM, on a balance of probabilities, knew of TVJ’s claim to an exclusive licence because of the extensive pre-games publicity engaged in by TVJ.64

(…) This court is in no doubt that CVM was sailing close to the wind. It took a deliberate and calculated risk in using material that to its certain knowledge was covered by the exclusive licence. The fact that it got a feed from the IAAF was legally irrelevant because it was never intended that the website should be used in the way CVM used it. The IAAF livestream was for the ordinary citizen who wished to enjoy the games. It was never intended for commercial exploitation.65

(…) CVM engaged in deliberate, calculated risk taking. CVM is not a neophyte in these affairs. In this court’s view, CVM, being an experienced broadcaster and having full knowledge of what is involved in broadcasting copyright/exclusive licence protected international sporting events, showed scant regard for the fact that TVJ had an exclusive licence.66

In light of these findings, the court made an award of US$40,000.00 in additional damages.

Conclusion